Molins de Rei is in the valley of the Llobregat river and stretches from the left bank of the Llobregat river to the mountain range of Serra de Collserola. Nowadays its population is 26,000 and is a part of the metropolitan area of Barcelona. It borders the neighboring towns of Papiol and Sant Cugat del Vallès to the north, Sant Feliu de Llobregat to the south, Sant Vicenç dels Horts in the west and Barcelona in the northeast. It is well connected to the Catalan capital, where it can be reached by train, bus or car in about 20 minutes.

The town has three hotels and many tourist apartments. Due to being well-connected and having competitive prices, they are a good option for a business stay or to make a quiet discovery of the environment. They also offer an alternative to getting to Barcelona quickly, by public or private transport.

The town offers its visitors history, tradition, nature, culture and gastronomy, with a rich architectonic heritage from various periods, a strong commercial, social and associative fabric, and a wide variety of services and restaurants, as well as popular festivals and cultural events which are referents in the territory.

CULTURE, HERITAGE AND LEISURE

Architectural heritage and cultural offer

Walking around the historical town center shows a rich architectural heritage from various periods to be enjoyed.

One highlight is the Palau de Requesens, with its Renaissance style, currently in the process of being restored to become an art and cultural centre devoted to the Renaissance. It is a municipal project in which the Catalan government and the European Union collaborate using the ERDF (European Regional Development Fund).

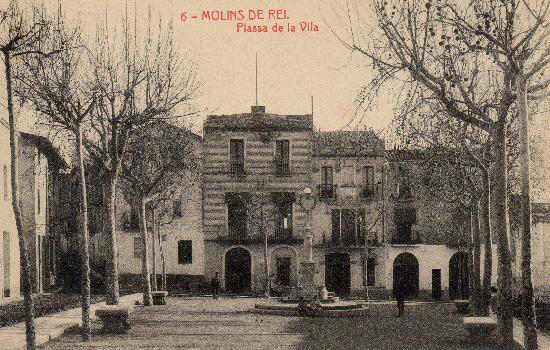

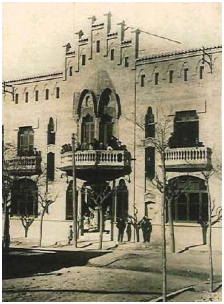

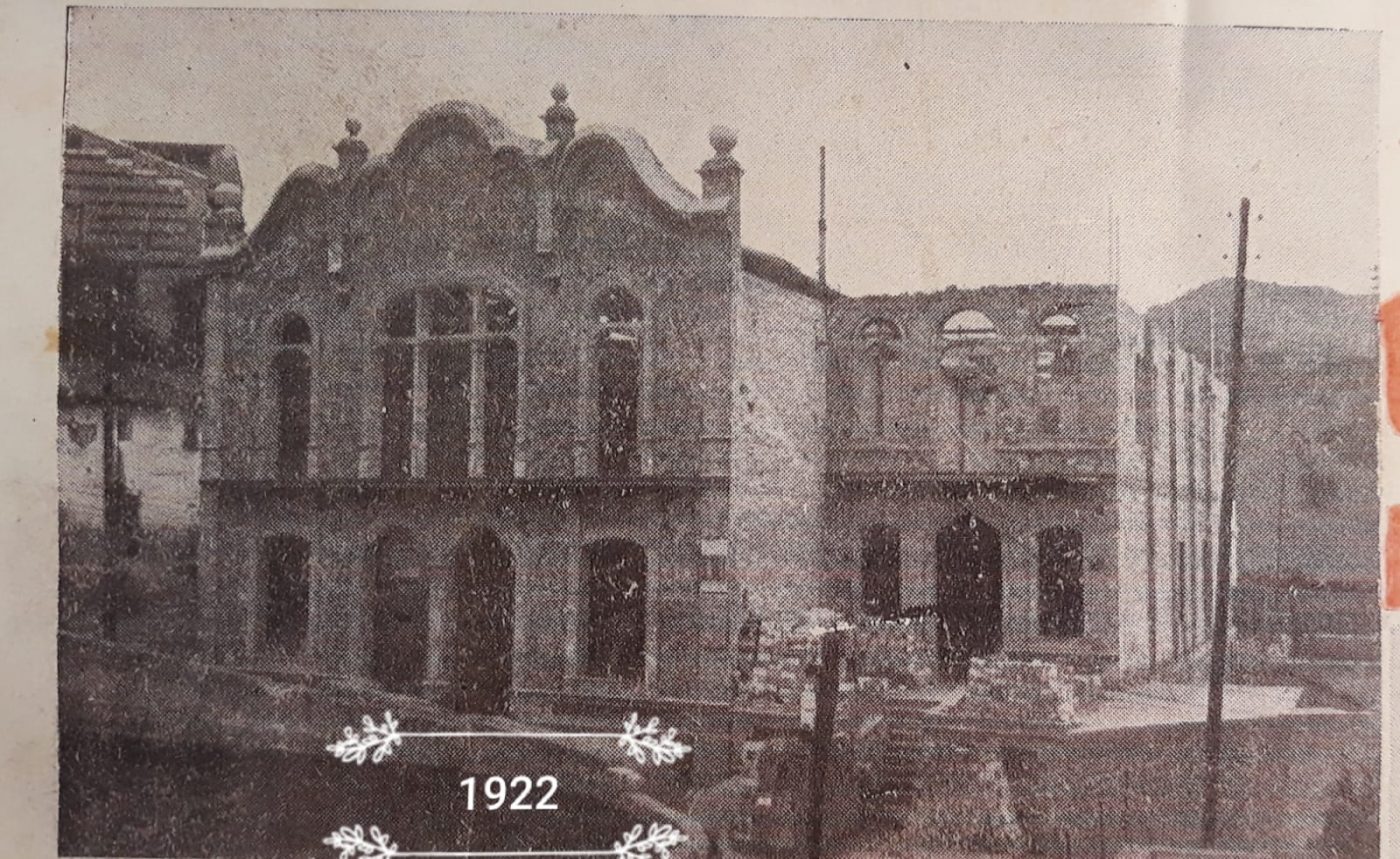

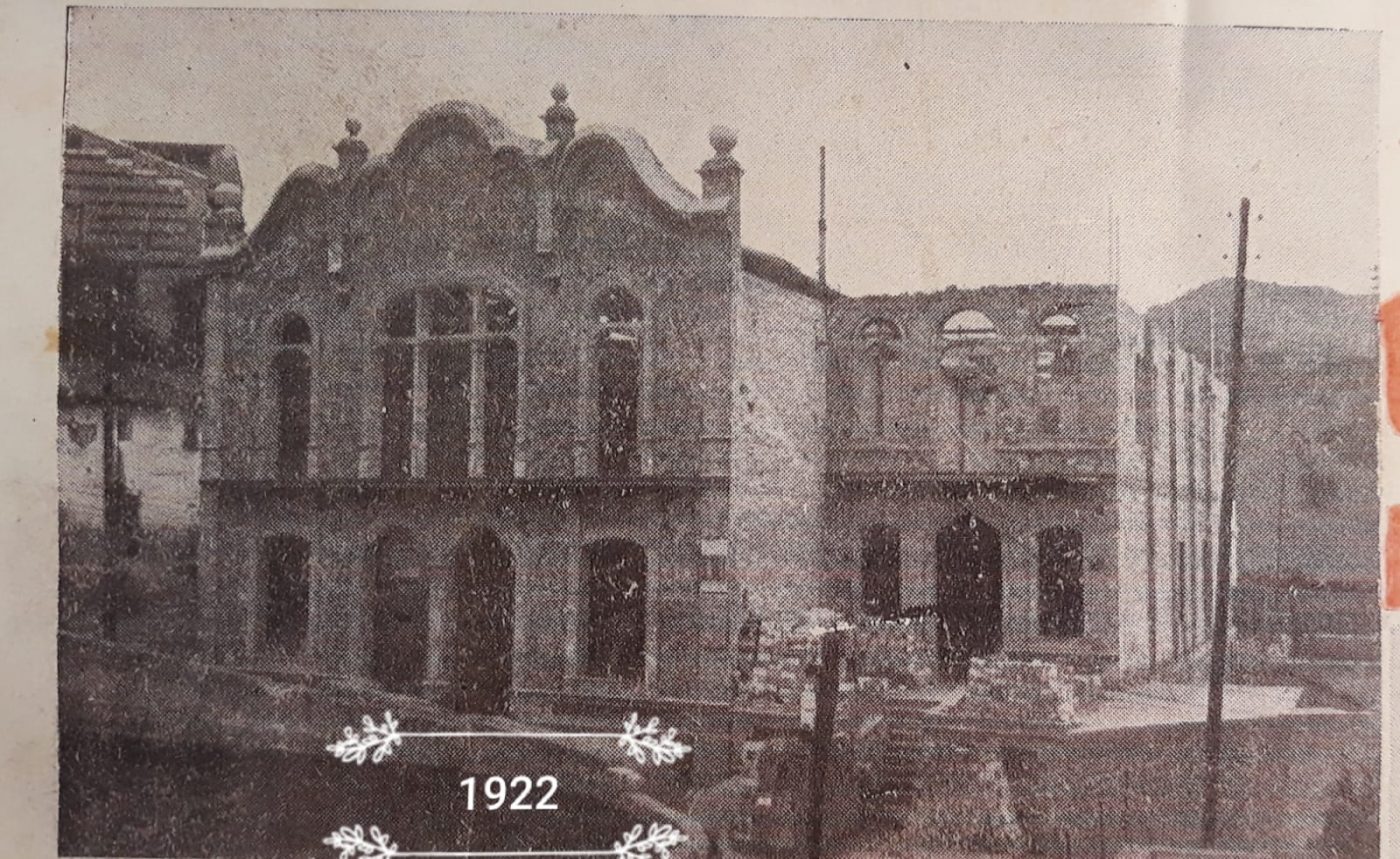

Ca n’Ametller and the Foment Cultural i Artistic, in Neoclassical style, or the Federació Obrera, in Modernist style, are other emblematic buildings of the town. And, of course, the Joventut Catòlica building, popularly known as la Peni, the main headquarters of our Festival. It was inaugurated in 1921, in the Noucentista period, but with an aesthetic inherited from Modernism. These facilities welcome a great variety of year-round activities: music, theatre, spectacles, conferences, conventions, speeches, networking sessions…

The splendid library el Molí, a finalist in the FAD2020 awards, from the old Ferrer i Mora textile factory, is also an space open to cultural and educational activities: as well as the book loan system (with around 40,000 documents), it offers a wide range of activities promoting reading and culture, such as narratives, workshops, shows, conferences, encounters with authors, reading clubs and technology training.

The museum of Molins de Rei holds a collection of archaeological materials found in excavations made in Molins and its surroundings. It also has architectural and sculptural elements from buildings such as the Palau de Requesens and the Castell Ciuró, and ethnologic materials from traditional trades, as well as from the pictorial art fund, with works by artists like Miquel Carbonell. Singular elements, such as the remains of the wooden piers of the old Charles III of Spain bridge, are also displayed. The museum was an initiative by workers of the textile company Can Samaranch. It was managed by the Associació d’Amics del Museu until the late 70s, when it became municipal property.

Lastly, we must mention both the Mercat Municipal, built in 1935 by Josep Badia and remodeled in 2007, and the Sant Miquel parish, inaugured in 1942 after the war had destroyed the old church, which shines because of its dome with 24 mosaics, made by Santiago Padrós.

La Candelera, tradition and modernity

Every first weekend of February, since 1851, the Fira de la Candelera has been celebrated, and it has become a traditional festival of national interest since 2002, and a fair inspiration to the country.

This emblematic Molinenc celebration has agriculture as its common thread, but has been incorporating novelties, combining tradition and modernity. It is the exponent of economic sectors such as gardening, agricultural machinery, livestock, wine, food, automobiles, car boot sales, collecting and crafts. It also hosts a wide range of socio-cultural and festive activities like the opening address, agricultural conferences, muleteer’s breakfast, contests, exhibitions, concerts, castellers, theatre, literary presentations, Giants, popular botifarrada (sausage meal) and automobile-related activities. The town organizations participate with their own booths, and children can enjoy the Fira Jove.

La Candelera is possible thanks to collective initiatives from the whole town, which for generations has put their efforts into this project of openness and hospitality.

As the old saying goes: Si la Candelera plora, el fred és fora (If the Candelera cries, the cold is gone) Si la Candelera riu, el fred és viu (If the Candelera laughs, the cold is alive), and we would like to complete it with… I tant si plora com si riu, a Molins de Rei veniu! (And whether it cries or it laughs, come to Molins de Rei.)

Festa Major de Sant Miquel, Carnaval and Festa dels Tres Tombs

The Festa Major of Sant Miquel Arcàngel is celebrated around the day of Molins de Rei’s patron saint, on September 29th. The town organizations get involved in a decisive way with the development of the festivity. Participating organizations include the colla castellera dels Matossers, els Bastoners, l’Esbart Dansaire, El Cuc, el drac l’Entxuscat, els Diables or l’Agrupació Folklòrica. However, the main invigorating parties of the celebration are the Camell and the Molins de Rei giants.

The Giants consist of two giant couples: the Gegants Vells Miquel and Montserrat, created in 1913, and the Gegants Nous Bernat and Candelera, created in 1988. The town giants and other groups from other towns get together on the second Sunday of the Festa Major. They also play a key role during the Carnival, representing the bourgeoisie’s dance which year after year is interrupted by the appearance of El Camell.

It is very difficult to determine the origins of El Camell, an imposing figure of fantastic physiognomy, the oldest document found dates from the end of the 18th century, although the tradition could be much older. This document explains that every year, around the Carnival dates, the village’s peasants built a terrifying figure to boycott the Carnival dance of the wealthy families of Molins de Rei. They built the body with parts of a cart and a blanket, and then placed the head of a dead horse with oranges in its eye sockets and moved the animal’s jaw through a crafty mechanism. The beast used to burst into the Carnival dance, causing people to run and scream. This tradition became so popular that the town’s square was also known as the Plaça del Camell. By now, you will have deduced that El Camell has nothing to do with a desert camel. It is named after the expression “fer el camell” (to do the camel), which in Molins de Rei has the meaning of “fooling around”. And so, the current Camell recovers and gives a modern reinterpretation to the old Molins de Rei tradition in the form of a giant fire beast. Since its recovery in 1981, in a post-Francoist context of reclaiming the streets as a festive and ludic space, El Camell has gained popularity in the town thus becoming one of the central events of the Festa Major de Sant Miquel and the Carnival, besides being one of the town’s most emblematic figures.

Every year, on the festivity of Sant Antoni Abad, the traditional celebration of els Tres Tombs is celebrated. Horses and carriages go out in a parade through the town’s main streets, and visitors bring their pets to be blessed.

Gastronomy and social, commercial and associative fabric

Molins de Rei shines for its social, commercial and associative fabric. It is an enterprising and leading town, thanks to its people. Two merchant associations gather more than 600 businesses.

The Mercat Municipal (built in 1935 by Josep Badia and remodeled in 2007), is economically active, and an incentive to create and revitalise new businesses. The Mercat plays a key role in the town’s configuration to make it more socially, economically and environmentally sustainable, and is the commercial locomotive of Molins de Rei Centre de Comerç. L’Aula Gastronòmica, a cooking school, the second one after la Boqueria in Barcelona, can also be found here.

The range of bars and restaurants is extraordinarily wide, with all kinds of cuisine, from traditional and local food (traditional masies-restaurants are a must) to fusion cuisine, imported from far away countries. They are one of the town’s strong points, and for this reason many people in the surrounding areas take an interest and enjoy the splendid gastronomic offer.

Furthermore, every year activities like the gastronomic tasting of la Fira de la Candelera or the tapas sampling fair Molins B de Gust. During the Fira de la Candelera, many restaurants offer coradella (link), a traditional dish served to the muleteers who came to show their products or livestock to the fair. Made from lamb entrails and served with wine, it is a rural dish, with an intense flavour and very energetic, perfect to withstand the most demanding of labour days.

Nature

Having a Mediterranean climate and forest making up more than 65% of its land, Molins is also one of the best doors to the green lung of the Parc Natural de Collserola.

There are a vast number of routes in the midst of nature, with interesting landmarks such as the Castell Ciuró, the hermitage of Sant Pere Romaní, the masia of Can Santoi and Santa Creu d’Olorda.

In Molins there are two distinctive morphological units: plain and mountain. The plain, along the left bank of the Llobregat, stands at a regular altitude of 20-30 meters above the sea level. The town’s historical center is located at the plain’s limit with the first mountain ranges.

Mountains make up more than 88% of the town, which is a part of the Collserola mountain range. The landscape has peaks of smooth shapes (puig d’Olorda, 434m; penyes d’en Castellví, 237m; serra de Can Julià, 236m; Mulei, 226m), separated by valleys where many brooks and streams flow.

At the mountain’s high part big pine groves of white pines and stone pines, combined with little areas of holm oaks, can be found. At the hollows there are hideouts of great beauty and botanic wealth.

Molins de Rei and metal music

Molins de Rei offers various dates that lovers of metal music cannot miss, thanks to concerts and festivals such as MOVE YOUR FUCKING BRAIN EXTREME FEST and CRASH DUMMIES METAL FEST.

All of this was possible thanks to the Metal Defenders association, which was born in 2002 in Molins de Rei aiming to defend and promote the aesthetic, social and cultural values linked to the world of metal music. The entity’s biggest and most extreme bet came in 2006, with the creation of a new free festival, the Move Your Fucking Brain Extreme Fest (MYFBEF), open to all lovers of extreme metal. This adventure initially began in the Parc del Llobregat, in a small format, and later moved to the iconic Death field of Molins de Rei (Avda. Collserola). After 15 editions and lots of effort, the “Move” has become a festival filled with the extreme essence of international and peninsular origin, a quality festival and a benchmark within the world of metal music.

For more information, visit the entity’s social media: @MetalDefenders (facebook and instagram) and @MetalDef_MdR (twitter)

14th edition of the festival (2018)

Photo by Roser Pascual Garcia

A CINEMA TOWN

Origins of its love for cinema and historical chronology

Apart from traditional festivals, the strong associative fabric of Molins is also behind the great cinematographic tradition of the town: in 1898 there were exhibitions of optic shows in pole tents located at Avinguda València with Pi i Margall. In 1900 they took place at the Cinematògraf Puig as well, located in the Carril 21 street (later the hotel La Lluna), and years later, in 1912, the cinema Delícies, property of the Roca family, was born. Founded by Jaume Bosch and Emili Port, it was managed by republicans and federalists and opened only on the weekends.

Lerrouxists managed the Les Columnes cinema from 1912, in 1914, Adrià Gual filmed the movie La gitanilla in Molins, and in 1918 a documentary about the Conserves factory was filmed. In 1921 started the cinematographic activity at the Foment, in 1924 at Federació Obrera, and in 1925 at the Joventut Catòlica. In the 1930s, during the Second Republic, avant-gardist films were shown at the Foment. In 1931 the first talking film was displayed: The Broadway Melody.

There would be many openings, closings and fusion of cinemas, as you can see in this timeline of the history of cinema in Molins de Rei, developed by Glòria Massana, together with other memorable moments in this evolution. A tour through the cinephile origins of the town can also be found.

The birth of TerrorMolins

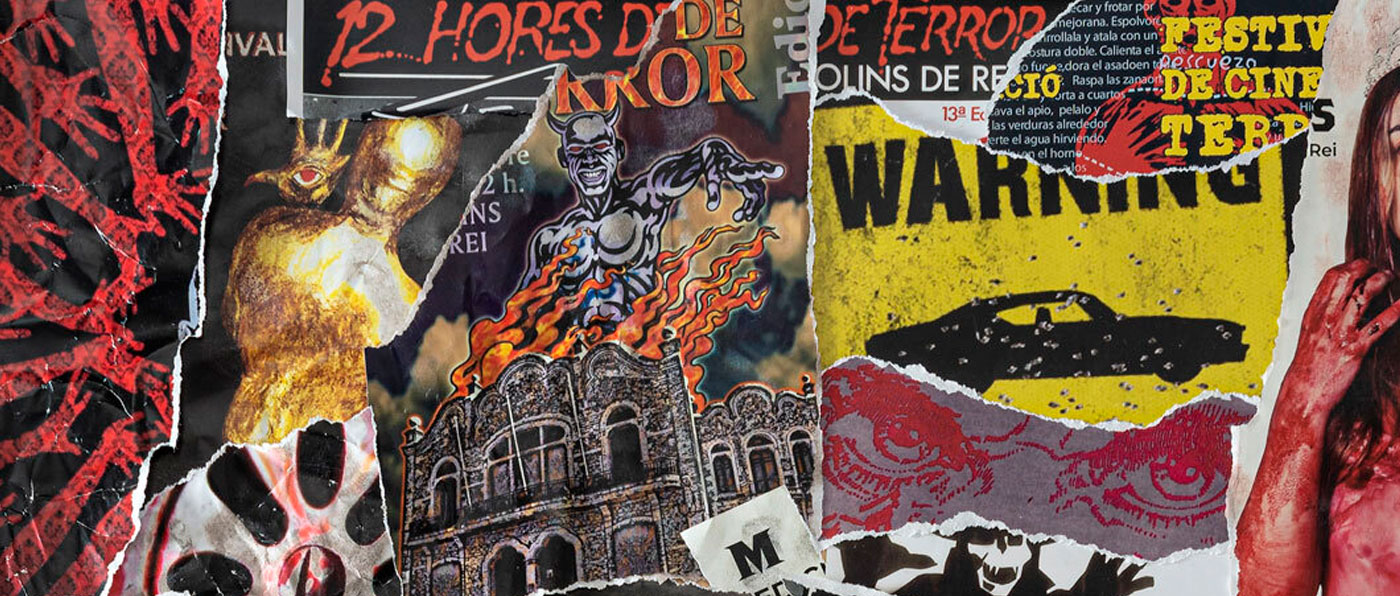

In 1970, the Savoy and Federació Obrera cinemas were closed, at a time of decline in the Molins de Rei cinemas. In this context we find the seed of our Festival: in 1973, the cinema club was looking for revenue to carry on with its stable programming, so they decided to create what was probably the country’s first horror film marathon. The first years were 16 hours in a row, eventually becoming the 12 Hores de Cine de Terror de Molins de Rei (12 hours of Horror Cinema of Molins de Rei). Success was immediate, as it was a new and fresh idea in an old and incarnate historical context, where the desire of experiencing collective events with this component of breaking emerged.

From 1979 to 1982 the first democratic city council and several town cinemas organized the Setmana de Cinema, with new creators, Catalan spoken cinema, independent films… At the 12 hours in 1979, between movies, horror happenings were introduced. After the feature of Tobe Hopper’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre, two hooded individuals equipped with chainsaws spread horror over the stalls. A police intervention took one of the actors of the performance and some members of the organization to the police station. The event could go on when the police checked that the chainsaws had their chains disarmed.

During the 70s and the 80s, the mysticism around the TerrorMolins marathon was formed, but the exhaustion of promoters and the public resulted in its abrupt end in the 1990s. In 1993 an attempt to recover the festival was made, but it was unsuccessful. The 12 Hours would enter a deep slumber of almost a decade.

In 2001, a group of fans decided to try again, hoping to make it new and different: the 12 Hours would not return alone, but accompanied by a showing of short films, and instead of a single day, they did it in three. Every year, more steps were taken: more days, more activities, more guests, more public…

The first decade of the new century is a benchmark that would end up being the event. Only two years after the reprisal, and following an agreement with the city of Sitges, the contest was renamed as a festival, because, despite the 12 Hours being the main event, they were no longer the festival’s only content.

The festival began to be recognized beyond its nearest borders, and as of 2010, the evolution was unstoppable: a flash fiction contest, the TerrorKids for the children, a showcase for secondary schools with students from all Baix Llobregat, the Molins Horror Games, Gastroterror, anthological exhibitions, publications, including guests and jury from around the world, new headquarters and spaces to accommodate new formats, and the Jornades Professionals for new talents and industries.

TerrorMolins was integrated into TAC or Terror Arreu de Catalunya (Horror around Catalunya), into Catalunya Film Festivals and into the European Federation of Fantastic Cinema Festivals, thanks to which our festival can award every year one of the renowned Méliès Awards.

The growth is exponential: more than 150 films per edition, 8000 in-person viewers and more than 30000 online, an average of 70 guests per year, almost 200 hotel overnight stays during 10 days…

With the Candelera as a historical reference, in Molins de Rei it is also a tradition inviting foreigners to enjoy the craziest celebrations. And at the Festival, the welcoming and pride spirit configured the vocation of internationalization and the will of being ambassadors abroad, all while enhancing creative talent, as if local, even better.

The festival proves its potential year after year, showing Molins to the world, with a different, cinephile, cultural and disinhibited look. Our spots have served to make us realize that we have a real cinematographic set in our streets, corners, atmospheres and squares. Molins de Rei is a great display window, a set from which shows the way we are and what we’re capable of doing. Paco Ruiz has reflected it through the various spots in the festival, and with its filmography.

A BIT OF HISTORY

From the Palaeolithic to the 19th century

In the Paleolithic period there is already evidence of a prehistoric settlement, and in the cova de l’Or de Santa Creu d’Olorda Neolithic remains have been found. The settlements in Puig d’Olorda, Plaça de les Bruixes i de les Argiles, dated in the 4th Century B.C., are from the Iberian age.

But to find the origin of the town as such, one has to jump forward to 1188: Alfonso II the Chaste, king of Aragon and count of Barcelona, ordered a certain “Joan dels molins” (Joan of the mills) to build a house with twelve millstones and a ditch. Initially, he could only build the house, and two years later the king asked Bernat el Ferrer (Bernat the Blacksmith) to forge the iron to run the mills. They were under the responsibility of Bernat el Ferrer, and one of the conditions was that he had to live there to take care of the buildings. It was that way that the town was born.

In 1208, Molins adopted the title of “vila”, with a license to have a parish and a cemetery: the bishop of Barcelona allowed a church (Sant Miquel) to be built in the highest part of the vila, which already had more than twenty houses. The residents farmed the land, tended to the livestock and worked many trades.

The Templar Knights Hospitaller, soldiers and monks at the same time, settled in Castell Ciuró (strategically located, with views to the valley of the Llobregat) to protect the townsfolk from the attack of their enemies, the Saracen.

The town was sold or mortgaged several times, until, in 1366, Berenguer de Relat, the counsel of the king Peter the Ceremonious, bought the town of Molins de Rei, castell d’Olorda and Castell Ciuró. Then, the town consisted of the house with the twelve millstones and next to seventy houses nearby. All the land and the houses were property of the king and the feudal lords.

In 1419, a group of townsfolk succeeded in gathering funds for the redemption of the feudality and to return the town in its integrity to the Crown. In 1430, Alfonso the Magnanimous gave the town to Galceran of Requesens, owner of the majority of the surrounding territories. Requesens converted the town into a barony and had a magnificent palace built, where his family spent long periods of time. In 1493, the Catholic Monarchs and Christopher Columbus stayed in the palace, as did many more prominent figures. In 1493, the Catholic Monarchs and Christopher Columbus stayed in the palace, as did many more prominent figures.

Another vastly unknown piece of information is: it was in Molins de Rei, on November 30th, 1519, where Charles V was proclaimed King of Romans and future Emperor Elected of the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1532, the empress Isabella of Portugal and her son, the future Phillip II, stayed in the palace. In the late 15th century, however, the Requesens family married into the Castilian nobility (the Dukes of Alba and the Dukes of Medina Sidonia, to name a few of them) and got distanced from the town. The barony gave competencies to the millers and authorized the opening of establishments, at the same time that rented the mills and the services, like the butcher’s shop, that it had controlled up to that point.

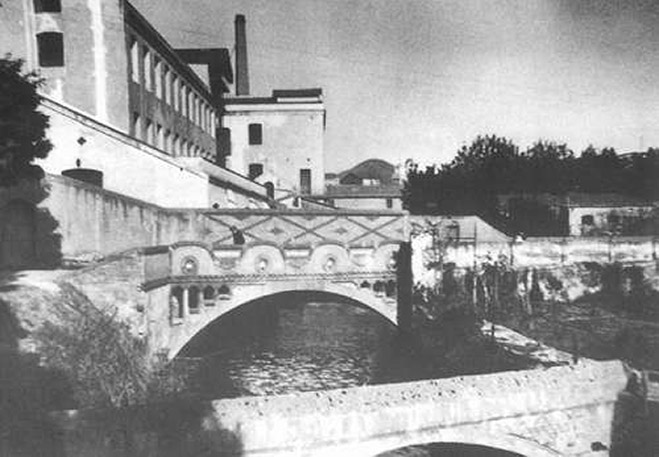

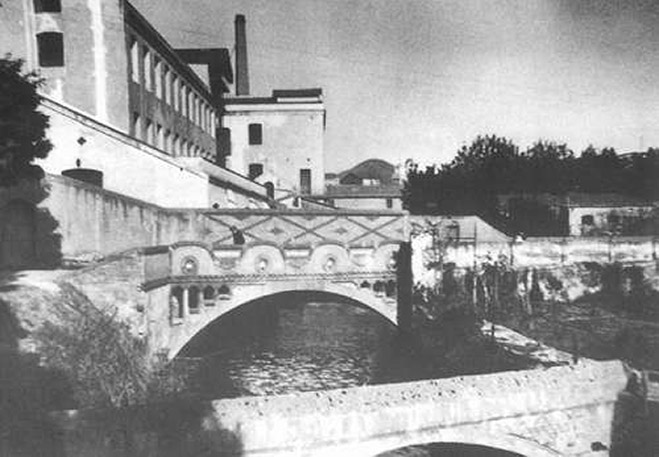

Another decisive moment for the town was the construction of the Charles III bridge, between 1763 and 1767. It was 334 meters long, had 15 arches and it was made out of red sandstone from the nearby mountains of Cervelló and Sant Andreu de la Barca. Molins gained strategic weight and went on to be a stop on the Madrid-Barcelona travel route. New shops and inns were opened, and the town became a hub for the nearby towns.

It was precisely for its strategic importance that the town suffered many battles over the Peninsular War. On June 7th, 1808, the army of general Schwarz, who had been defeated in the battle of Bruc, looted and set fire to Molins. A couple of weeks later, the troops of general Saint-Cyr occupied the land between Molins and Vilafranca. There were numerous casualties and grave damages to the urban structure were made. The damages to the Palace of Requesens caused its division into lots, which shaped what would be the Major (main) street.

The Third Carline war caused new lootings and fires, but in 1874, the wars weren’t the only event that upended the local economy: occurrences like the strikes in the emerging industry and the phylloxera plague, which arrived at the end of the 19th century after ravaging the French vines and the ones in the north of the country, also influenced. The plague was a hit for the local agriculture, and in fact, destroyed the town’s vineyards.

From peasantry to industry

Molins de Rei was an agrarian town until well into the 20th century. Like the rest of the country, peasantry had been historically the main economic sector, although by the end of the 19th century the industry was beginning to grow. The first major factory was the textile factory Ferrer i Mora (known as the Mill) in 1858.

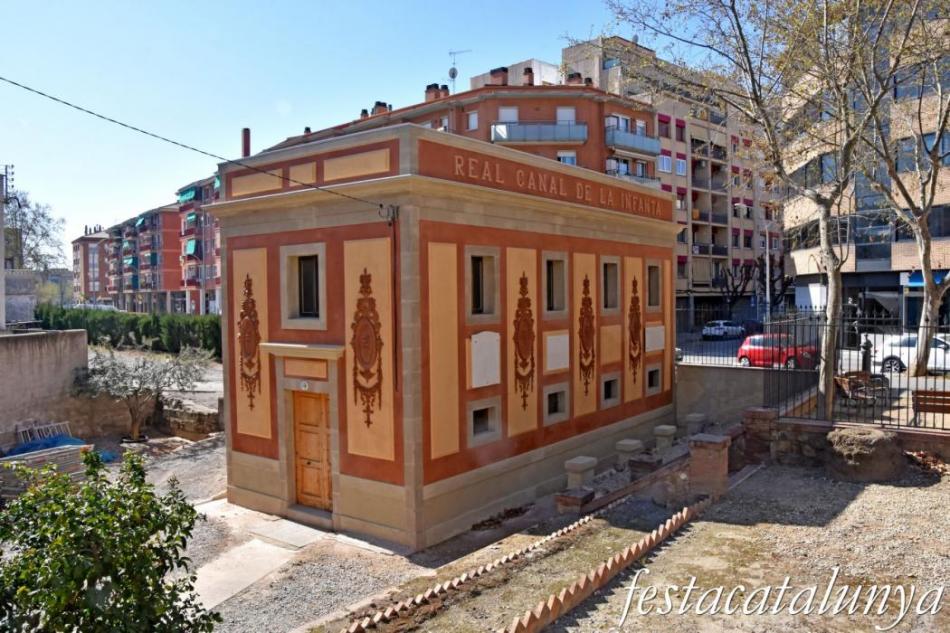

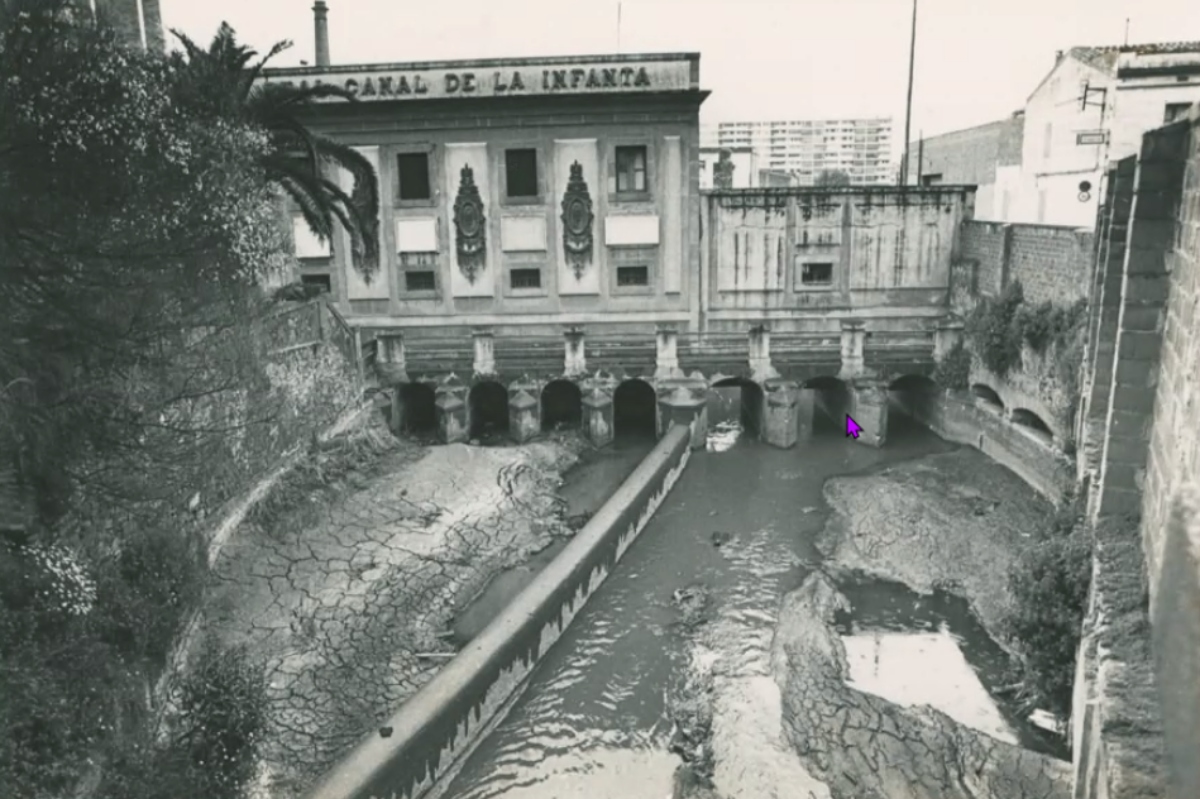

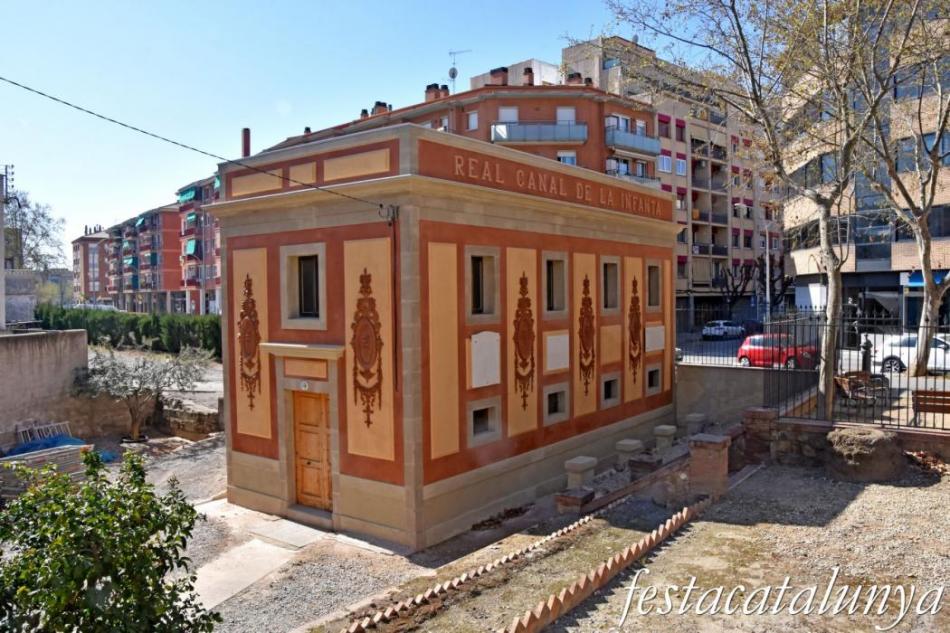

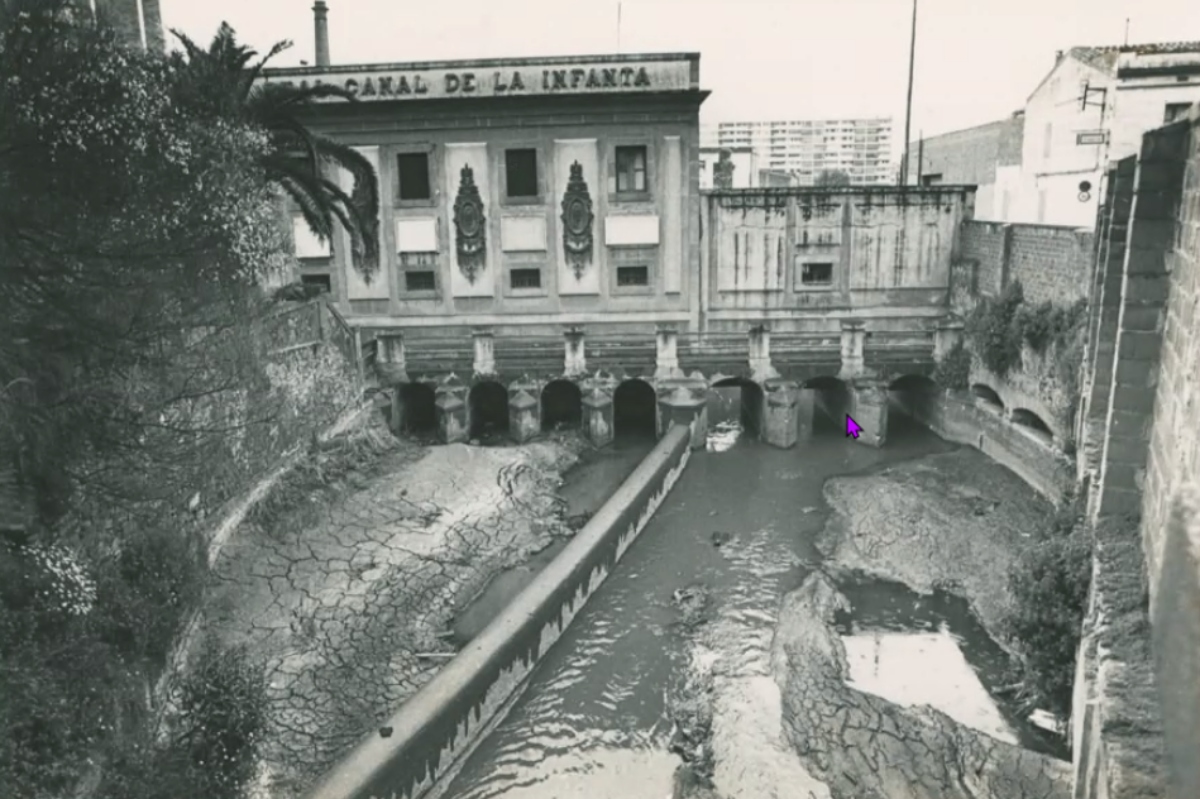

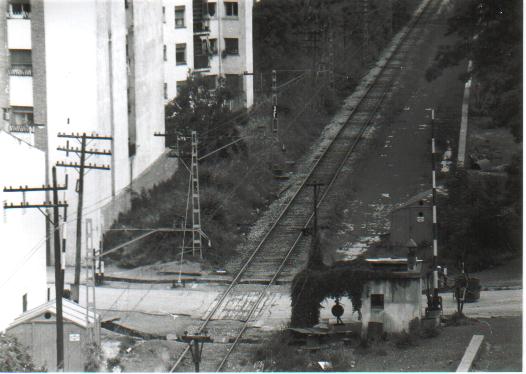

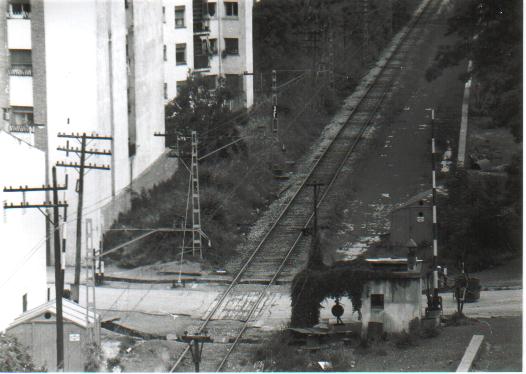

Two turning points were the construction of the Canal de la Infanta in 1819, with new irrigation networks, and the inauguration of the railway in 1855. These infrastructures favoured economic development.

The Canal de la Infanta, a 17.420 km canalization of water from the Llobregat river, supplied around 4.500 hectares of fields in the Lower Valley of the region, starting in Molins and going through Santa Creu d’Olorda (absorbed in 1916), Sant Feliu, Sant Joan Despí, Cornellà and L’Hospitalet, ending in Sants (absorbed by Barcelona in 1897). The civil society of Baix Llobregat and Barcelona had been asking for an infrastructure of this type for centuries. In fact, the first canal was built in 1188, el Rec Vell, which started at El Papiol, supplying flour mills on the left side of the Llobregat, and ultimately leading to our city’s birth.

Going back to the beginning of the 19th century, the Peninsular War had drastically affected the crops and therefore changed the way people lived, especially because of the skirmishes that took place between the retreating French army and the opposing guerrillas along the Llobregat riverbed, between Molins de Rei and the mouth of the river. The construction of the irrigation canal was a priority, and the bourgeois elites put pressure on Ferdinand VII, who agreed to abolish the monarchy’s exclusive right to build canals. The financing of the new canal was private, but the convulsive political context made it necessary to find public support, and it was Francisco Javier Castaños, Captain General of Catalonia, who was the main advocate of the project, which initially had his name. Its name was changed in 1819, when it was inaugurated by the Infanta Luisa Carlota, a year before the construction works were completed. The promoters of the canal, mainly owners of fertile dry land, converted it to irrigated cultivation. Cereals (wheat, oats and barley), pulses (peas, beans, chickpeas and lentils) and fruit trees (such as apple and pear trees) continued to be grown, but, due to the water being within reach, the productivity was boosted from one harvest a year to three or four, with the consequent population growth to supply the labour needed to exploit the land.

New crops such as corn or rice were introduced, with higher commercial margins than the traditional products, and the energy generated by the canal’s thirteen waterfalls made the industrialisation of the area possible. Since the canal water was taken from the drainage ditch of the mills and the factories of El Papiol and Molins de Rei, the owners of these lands claimed compensation for using their own water, and obtained the exploitation of some waterfalls as compensation.

The intensive development of agriculture and the population growth called for new transport services for both people and agricultural surpluses. In 1854 the Barcelona-Molins de Rei-Martorell train line was inaugurated. This railway line was parallel to or coincided with the canal’s route in many parts, which led to some conflict with the owners. The success of the canal was so big that it was replicated on the right side of the river to transform the lands of Sant Vicenç, Santa Coloma, Sant Boi and El Prat into irrigation.

The first Molins de Rei industry was the textile factory Galtés, in 1830. It initially had 13 manual looms. In 1850 there were 37, and 56 people were working there. The first large mechanised industry, founded by Josep Ferrer i Mora in 1858, had over 3.200 workers and 100 mechanical looms powered by the hydraulic energy provided by the Rec Bell. Can Coll, Can Iborra, Can Malvehí, Can Samaranch, among others, would also join the same activity. The steam, gas and electric engines of the Industrial Revolution ended the dependence on hydropower, and so, the decline of the canal began.

The Catalan industrial development of the late 1800s had also reached Molins de Rei. In 1890, with a population of 2935, there were 52 shops and 12 factories. The main industrial branch was the external capital textile. At the end of the century, the Ferrer i Mora factory installed the first steam machine to substitute hydraulic force, which had moved the mills for six centuries. At the same time, vegetables and fruit trees received a boost, and the annexation of part of the former municipality of Santa Creu d’Olorda in 1916 gave a new boost to agriculture, which would reach high export levels during the 1930s. In the 20th century, factories and houses occupied farmland, and Molins became an industrial town.

A turbulent 20th century

In this context of economic growth, the wave of Fourierism that travelled throughout the country in the mid-19th century also left a print in the town. The new partnerships, many of which have assets, channel social claims and articulate the cultural offer.

In 1918 the Federació Obrera (Working Federation), an heir to the Les Tres Classes de Vapor trade union, was created, and it would be despoiled by Franco’s dictatorship before being returned to the town. The Joventut Catòlica (Catholic Youths) was constituted in 1879 and in 1921 a new building (main headquarters of the festival) was built. The Foment Agrícola, Industrial i Comercial (nowadays Foment Cultural i Artístic) was born in 1920 and in 1923 and a new building largely sponsored by the bourgeoisie of agrarian origin was inaugurated.

Enllà, Festa, Camins, Germanor and Espartacus are the main headings of the first half of the 20th century. These magazines served as the spokesperson for the entities, often with heavy political burden. Unfortunately, the Spanish Civil War caused a deep trouble in the everyday life of Molins de Rei, as it did to the rest of the country.

The urban structure broadened to new zones at the other side of the tracks, and a canned food factory, that would end up naming the new suburb, was constructed, as well as a new market in 1935 and a school inaugurated by Alfonso XIII. The annexation of new neighbourhoods to the old town, the first of them being la Carretera, accelerated the town’s expansion.

During the Spanish Civil War, FAI (the Iberian Anarchist Federation) killed six townspeople, dynamited the church of Sant Miguel Arcàngel, destroying its archive, which dated back to the 16th century. The Francoist troops entered Molins on January 25th, 1939, and on February 4th, established the town major.

The industry was revived during the very hard post-war period. The immigrated population from Andalusia, Múrcia and Extremadura found jobs in factories like Samarach, Malvehy and Torra Balari, which markedly increased their production. The strong migratory waves, much higher to the ones that took place in the early century, are located in newly built areas such as Can Graner, Riera Bonet, l’Àngel and el Canal. In the 1960s and 1970s, the population growth rocketed until it doubled: Molins went from a population of 7364 in 1936 to 14460 in 1970.

As an interesting fact, swimming was allowed at Canal de la Infanta until the mid-twentieth century. The number of irrigated hectares steadily declined and, as the city grew, the infrastructure was integrated into an urban environment. In time, the canal’s water flow subsided and became increasingly more polluted due to the lack of funds to prevent waste from the Anoia river and the Rubí creek from flowing. During the seventies, towns surrounding the canal began covering and diverting the water. Nowadays, although the water cleaning process of sewage treatment plants, the constant city development puts at risk the small number of grasslands between Molins de Rei and l’Hospitalet de Llobregat.

The 15-arch bridge had resisted the bombings from Franco’s Nationalist faction, but the massive extraction of sand and gravel from the riverbed undermined its foundations. On December 6th, 1971, after a pillar collapsed, it dragged two arches. There were popular mobilizations to save the bridge, significant as a collective consciousness still in the midst of the Francoist era, but the authorities decided to demolish the remains and a new bridge was built.

Franco’s regime and the Church still controlled the publications and cultural manifestations in the late Francoism but, with the transition to democracy and the collective longing for freedom, new initiatives of festive and cultural participation came: the recovery of El Camell, a fire throwing monster of the late 19th century, the celebration of Carnival and the popular participation in the Festa Major brought a much-needed breath of fresh air, once again emphasizing the strength of the Molins de Rei associative fabric.

In the 80s and 90s, the development of urban planning in the 1976 Pla General Metropolità, with new neighbourhoods like la Granja and Riera Nova, became the new demographic impulse that will bring Molins up to a population of 25000.

Historically, the town has changed its name twice, due to political reasons: in 1873, during the First Republic, it adopted the name of Molins del Pont (officially, del Puente). A year later, with the arrival of the Bourbon Restoration, it recovered its traditional name. During the Civil War, it went on to be called Molins de Llobregat, following the policy of eliminating monarchic and religious references from towns and cities. With the restoration of the Generalitat de Catalunya in 1981, the town’s official denomination was finally catalanized.

Witch hunts in Molins de Rei

In January 2022, Catalonia’s Parliament joined the “No eren bruixes, eren dones” (They weren’t witches, they were women) campaign, which acknowledges women accused of witchcraft as gender-based violence victims. The campaign is pushing to raise awareness of the adversities these death-sentenced and repressed women had to endure. Consequently, reporting this institutionalized femicide reintroduced the issue, surfacing studies that conclude the persecution in Catalonia was more brutal than in other parts of the country, like Galicia, where folklore history is generally widespread.

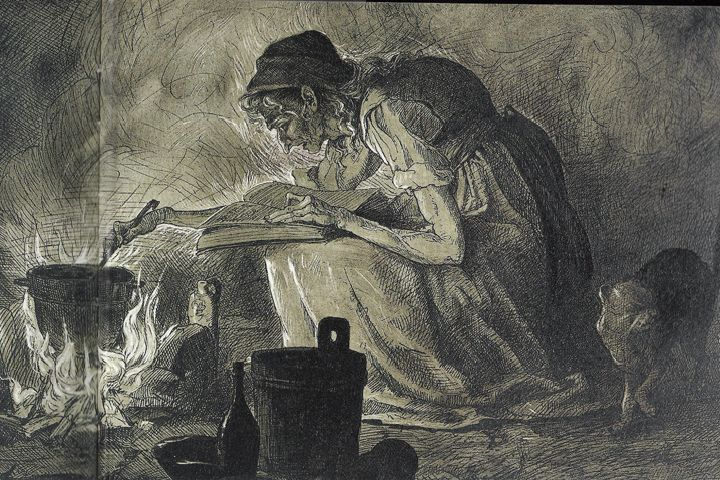

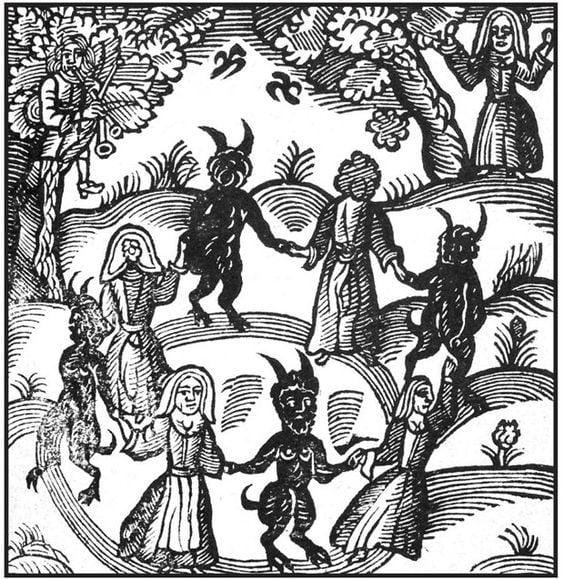

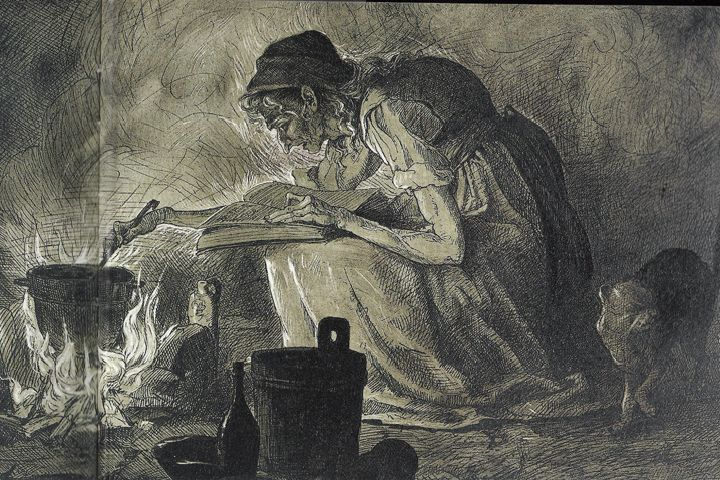

According to some religious texts, witches had supernatural and magical qualities that could arise both innately or through a pact with the occult. Historically, witches have been accused of infanticide, having weather-control abilities, celebrating Black Mass, casting curses, and gathering for Witches’ Sabbath or Akelarre (Basque Country). The Witches’ Sabbath is a purported feast where witches had intercourse with the Devil, who appeared in goat form. European witchcraft is often linked to Neopaganism, but in Western Countries, it has also been associated with Medieval Devil Worship. These women groups had common traits: their mystic symbology, seductiveness, and rebellion against authority. That made witches influential pop culture and folklore representations in our country.

In Catalonia, the first witch trials took place during the fourteenth century. The outcomes were moderate: warnings, fasting periods, or pilgrimages to Montserrat. The first significant trial took place in the fifteenth century in Amer, Girona, yet, the most alarming trials happened during the seventeenth century when accused women were persecuted, tortured, and executed. Practicing witchcraft, like brigandage and producing counterfeit money, would put a person at risk of being outcasted. Hundreds of women were sentenced to death penalties —in Europe, more than half a million women were burnt at the stake due to generalized panic—. Although some warlocks, men who practice witchcraft, also suffered the consequences of the persecutions, they were a small minority —80% of the people executed were women—. Catalonia was one of the most significant European witch hunt hot spots. The most notorious trials were those that happened in Vic, from 1618 to 1622, followed by “la bruixa Napa de Prats del Lluçanès” (the Napa Witch of Prats del Lluçanès). In Catalonia, witches were judged as common offenders and they were hung instead of burnt at the stake. Burning witches was a common practice of the Inquisition, which was scarce in Catalonia. Witches were usually hung in the main squares of villages or on gallows set by roads, where they would be left hanging as a warning. During the eighteenth century, the French Encyclopaedists’ influence stopped most persecutions, although some trials still took place during the nineteenth century.

The constant backward and forward of people crossing the Pyrenees from Occintanie or the mayor’s absolute ruling power over the population are two clear examples of the different determining factors when defining the causes of the vast amount of deaths resulting from witch trials. Women accused of witchcraft were described as independent women with herbal and healing knowledge, considered a threat to the institutions, and outcasted from society. Incidentally, this description is far-fetched from the popular image consolidated in pop culture nowadays: the old witch with a hunchback and a broom.

Molins de Rei, along with other county municipalities like Martorell and Collbató, is part of the map of Catalan witchcraft. Rumor has it that the witches from Molins de Rei went to one of the forest clearings to practice their magic. This clearing is known today as “Pla de les Bruixes” (Witches Clearing), and it’s located right off the road leading to Sant Bartomeu, next to the Iberian-Roman ruins and the motocross circuit.

Most defendants in the Catalan witch trials were accused of using dark magic to injure, cause disease, or even death. Another little-known but commonly used Dark Magic practice was tying all sorts of knots —hair, ribbon, fabric, and plants— to cause infertility to couples or livestock and avoid domestic violence, infidelities, and marriage problems. Back then, both ecclesiastical texts and written law stated the consequences of such practices. This evil view of Popular Magic was quickly spread through Moralist Literature and preachers who, using their speeches, caused the population to believe that Magic wasn’t just superstition but a pact with the occult. One of the victims of these procedures was Eulàlia Llopart, born in Molins de Rei, who had to face the Vegueria of Barcelona in 1424, accused by her lover of tying him with strange knots and using magnets to stop him from abandoning her.

Besides the heretic component and the hexes, these so-called witches were also accused of trespassing into homes at night to choke people, kidnap children, steal from pantries, and break into cellars. A clear example of these “night visits” took place in 1304 when a woman known as “la Salvatge” (the savage) was accused by the Molins de Rei parish. (source: Pau Castell Granados; “Orígens i evolució de la caçera de bruixes a catalunya”).

Legends say the last Catalan witch lived in Can Mallol, an old farmhouse between Molins and Vallvidrera. People called her la Teia, and her powers allowed her to shape-shift into a dog. She was an independent woman who worked the land by herself. Her independence caused a great deal of rivalry and jealousy among nearby farmers to the point where “el vell de can Busquets” (the old man from Can Busquets) went to the house to pester Teia’s mother who was visually impaired. According to the farmers, Teia shape-shifted into a mangy dog and went back to Can Busquets to wallow on the old man’s bed. As he laid down later that day, he started itching and had to rush to the well where the dog was waiting to push him in. There, a big black dog pushed him and the old man drowned to death. The farmers in Vallvidrera and Santa Creu d’Olorda went back seeking revenge, but according to the legend, Teia, still in the shape of a dog, attacked them, ran away, and was never seen again.

Oddly enough, in the mid-XIX century the person living in Can Mallol was Enriqueta Martí, known as “la Vampira del Raval” (Raval’s Vampire). She was accused of killing children to drain their blood to sell it to rich people with Tuberculosis. Most of these popular legends were used to discredit women who were considered out of the norm. In Martí’s case, only one kidnapping case was proved. The story spread by the media was likely to be a means of hiding a prostitution ring that had many influential people involved.

What is clear is that Collserola is considered an area for those passionate about witchcraft and the occult: the Chapel of Santa Creu d’Olorda, the Encantades (bewitched) Mountain, el plà de les Bruixes (Witches Clearing), plaça de les Bruixes (Witches Square)…

The legend of

LA PLASSA DE LAS BRUIXAS

article | original text | translation

(language: catalan)

sources:

Molins de Rei del Passat (1 – 2)

Viquitexts